How many 'r's are in 'error'?

Why technical knowledge matters in the legal sector.

Here’s an exercise for you: ask ChatGPT how many ‘r’s there are in ‘error’.

…What? It produces an expected answer? How times have changed…

Ok, switch your model to GPT-4o if you’re on a plan that permits it. Otherwise, you’ll have to trust what happens next: ask the Large Language Model (LLM) the same question again.

It said 2 ‘r’s right? How odd… what’s changed between now and then? And why might understanding this error help improve your AI literacy? Let’s connect these questions below.

How many ‘r’s are in strawberry?

About a year ago, I had been introduced to what tokens were and how they worked by a Computer Science PhD student (it was a beautifully detailed introduction), but did not fully grasp the relevance of this understanding until I stumbled upon an innocent comment on a not-so-innocent Instagram post (forgive me for not citing its source lest I cause political outrage):

“Genuine question why are people using [deepseek] over chatgpt?”

To which another commenter responded:

“ask gpt how many rs in strawberry and then ask deepseek the same question. genuinely the difference should make the difference clear”.

Right, I thought. Well that’s just silly, isn’t it? How could models trained on billions of sources falter at a counting task? Fortunately, my knowledge of tokens bubbled to the top of my thoughts, exactly at the moment I realised: I’ve seen this before.

Tokens are how the input you provide to a model gets processed. These tokens aren’t words or letters; they’re sequences of text. When you see the word ‘error’ you may think that a model will see ‘e-r-r-o-r’, when in fact, ChatGPT’s tokeniser recognises this as one token: ‘error’. It breaks ‘strawberry’ down into three tokens: ‘str’, ‘aw’, ‘berry’. These tokens are converted into numbers to be processed – for instance, ‘berry’ is ‘19772’. So imagine being asked, ‘how many ‘r’s are in [3504, 1134, 19772]?’ An LLM will attempt to reconstruct the word ‘berry’ and would stumble upon rebuilding those letters into a sequence of numbers, replying with an incorrect count. A classic case of ‘hallucination’ – a model giving false responses. It’s fascinating how LLMs were able to associate one ‘r’ to ‘berry’, let alone two!

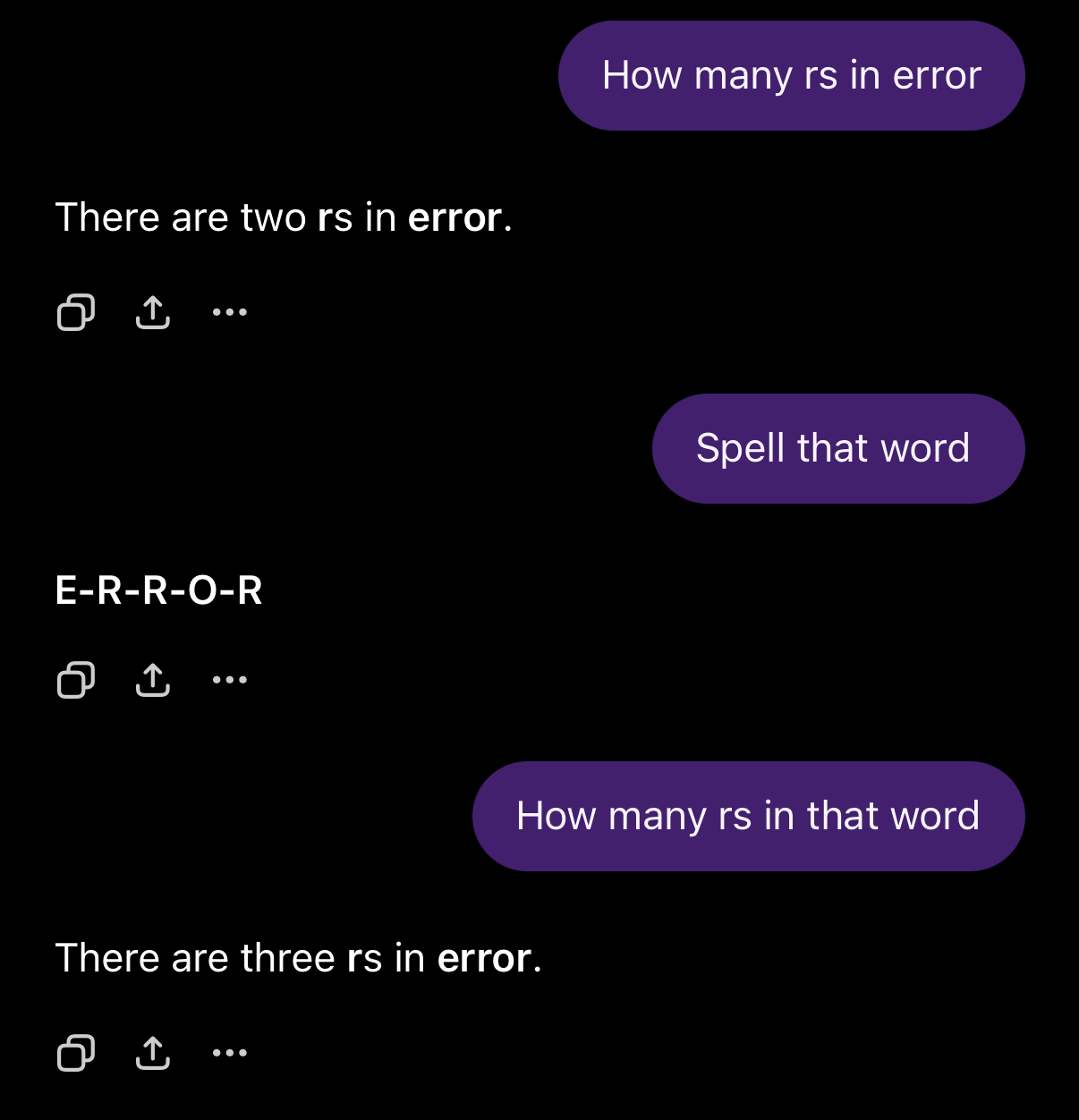

So how have recent models (ChatGPT-5.2, Claude’s Sonnet 4.5, and others) been able to circumvent the strawberry problem? It’s suspected that they now implement a ‘chain-of-reasoning’ strategy, getting models to ‘think’ a few extra steps to spell out words before they answer similar questions. Here’s an example of brute-forcing this behaviour on the earlier 4o model in ChatGPT:

But the underlying principle remains – LLMs don’t ‘think’ in the same way we do. They don’t perceive information in any way similar; even if their capabilities (quite deviously) convince you otherwise. They are still following the ‘input -> calculations -> output’ model, even with complex embeddings (i.e. knowing ‘strawberries’ are a ‘fruit’) that eerily resemble our own pattern recognition. Once you begin to appreciate this separation, you can start to understand why legal AI is so difficult to implement – we can’t reliably predict an LLM’s output.

The Wrapper Problem

Many legal AI companies have grown substantially over recent years, bringing specialised large-language capabilities to the legal space. However, they have been unable to completely prevent hallucinations within their products. Most legal AI vendors use existing foundation models to provide their services, thus, if ChatGPT-4o is the model adopted, how can it be prevented from making the same mistake as above? How can value be justified if these services fundamentally interpret information in the same way as general LLMs?

This exact problem cropped up a few months ago, starting in Reddit and spreading far and wide (as far as LinkedIn and a few legal AI reporting sites go), where a user claimed that a top legal AI product was essentially a ChatGPT wrapper. Here, ‘wrapper’ means that the AI product being sold adopts ChatGPT’s foundation model. Put simply, their AI capabilities are powered by another company’s LLM. So, what makes this scandalous? Many legal individuals felt as if the value of legal AI tools had been oversold and overhyped – why should they pay more for something that’s essentially ChatGPT with extra steps?

Whilst I won’t argue for or against actual costs, I do believe there is value in these legal AI products, even if they’re just ‘wrappers’. With Sam Altman previously revealing that it cost over $100 million to train ChatGPT 4, how could one reasonably expect legal AI companies to keep up with the ever-increasing costs of LLM development, whilst also attempting to successfully beat the top general model providers at their own game? By the time they would’ve created a domain-specific model, Google may have released their next instalment of Gemini that not only is faster, more responsive, and more accurate – it would also come at a lower cost. In a world moving so fast, I can understand why AI companies opt into adopting the best available technology. After all, you could call one of my favourite products, Typeform, an HTML forms wrapper. But it’s how it provides a clean, responsive, and user-friendly product, able to integrate into my customer outreach workflows, that gives it its value – not the technology that powers it in the backend.

It seems the actual ‘wrapper problem’ isn’t the lack of model specialisation, but rather, the lack of transparency into the value you are receiving with a legal AI product. So how can you navigate this moving forward? What can you look out for?

Most legal AI vendors will offer products built on Gemini, Claude, ChatGPT, or a selection of any of the three. However, what distinguishes these products are the actions they take on your documents and workflows, rather than how they’re being processed. As before, we still can’t predict the output of LLMs, but we can build a robust architecture that surrounds them to shape and guide their outputs. Look out for how legal AI products treat security, how they specify document timeframes and reminders, or how they adapt to your organisation’s legal reasoning style. Test the guardrails they put in place – how do they apply in edge cases? Do their workflows enable you to automate your most repetitive tasks, or integrate research tools from your knowledge bases? But most importantly, you should be examining and challenging their limitations. See how long it takes before something breaks. We’re all participating in this era of AI experimentation – rapid feedback is what will push us forward.

All this seems to point to a more pressing need – the legal sector requires greater transparency into AI technology, which can only be acquired through improving its overall AI literacy.

A growing need for AI literacy in the legal landscape

If you’re wondering what motivated me to finally start writing this article, it would be the growing distrust of LLMs, particularly in the legal space – leading individuals to boil them down to ‘pattern recognition machines’ in an attempt to demystify their allure and push back against claims surrounding their value. I completely understand this – sometimes I need to remind myself that it’s all smart computing, not a smart computer. But dismissing AI models as ‘prediction machines’ slows much needed innovation in the legal space. Just as commercial awareness has been touted as one of the most important skills you could have (it has been useful, in all honesty), AI literacy is just as, or perhaps even more so, important.

Whilst I refuse to limit my blog to only focus the legal AI space, instead opting to speak on anything along the spectrum of legal and tech, one of my main aims is to empower my readers to approach new territory (whether it be legal or tech) with confidence and curiosity, rather than fear and misunderstanding. My first step is to share my learnings on what it means to be ‘AI literate’ in the modern day, particularly for those in the legal sector. For instance, this may involve me (attempting) to break down more complex concepts – such as the tokenisation issue above. Other times, I may be inclined to share recent AI news that has potential to shape how legal operates, to prepare for those ‘what ifs’. And hopefully, something fruitful will slowly start to sprout from this shared understanding.

But for now, at least we all know how many ‘r’s are in error.